Ole Oleson and his wife, Polly Philena Patton Oleson were early pioneers in Garden Home. They owned a number of properties in the north Oleson Road area. They had one son and seven daughters who married into various Schalk, Wolf, Stark, Ruhl, Ames and Dayton families. The Stark family later married into the Bighaus family who have given us these stories. The following stories were developed by descendants of the Simmons-Patton-Oleson families to share their family stories and to describe and illustrate their early history coming West. See other Oleson family stories.

Polly Philena’s father was John Patton whose early gruesome death is described. This story begins with her mother, Margaret Lovisa Simmons who was widowed early and raised four children, including Polly. John Patton’s father was Mathew Patton, an early entrepreneur and philanthropist who is buried in the cemetery across from the Portland Golf Club. Mathew is spelled with one T in early accounts and on his grave headstone; however two T’s are often used in the stories below. See Mathew Patton for his story.

William and Mary Patton came out on the 1850 wagon train to Oregon. Mathew is reported to have brought a flock of sheep across the plains in 1847. The Simmons family came later in a 1853 wagon train.

Thanks to Debbie Bighaus-West for sending us this family history authored by family members, and is used with her permission.

Reviewed by Elaine and Tom Shreve, 2016

[Correction 2020-08-13: Thanks to Stephenie Flora for the clarification that Matthew Patton (1805-1892) was the son of Robert Jesse Patton and Eleanor Evans. William and Mary Patton who emigrated in 1850 were not his parents as previously stated in this story.]

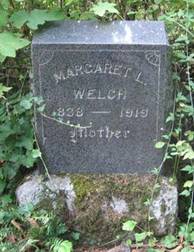

The Life & Times of Margaret (Simmons) Patton Mills Welch, 1838-1919

[This article was written by Granddaughter Reta Welch in 1986. Margaret was the mother of Polly Philena Patton Oleson.]

Margaret Lovisa Simmons was born 4 May 1838 in Linn County, Iowa, a daughter of Benjamin & Francis Ann (Sherwood) Simmons. (Francis was a descendent of the North Carolina Sherwoods) The Simmons family was among the first to arrive in the Cedar Rapids, Iowa area, where a settlement was in its early stages. Margaret attended school in Iowa and learned to read, write and chipper (math). For her day, she had a good education.

Margaret was 15 years old in 1853 when she and her family crossed the plains to Oregon. Their wagon train was made up mainly of Simmons, Sherwoods and Crows, who were all relatives. She walked all the way except for a few times at the start of the journey when she sneaked a ride on the wagon tongue between the oxen. It was very warm and comfortable, as the big oxen walked along swaying her gently on the tongue between their warm bellies. One day, shortly out of St. Louis, she went to sleep and her father caught her napping between the oxen. That was the end of her ride.

After that she walked all the way to Oregon, herding the cows and young stock. It was September when they got to the Umatilla Country. The Indians had just harvested a big crop of little dry hard white peas.

These peas were the staple of their winter diet. They were very glad to trade peas for things they liked from the white people. The most popular items were sheets and shirts. The wooden butter bowl that belonged to Margaret’s Mother was the unit of measure; so many bowls of peas for a shirt, so many for a sheet. Margaret’s Mom guarded her butter bowl very carefully as she had several times caught Indian women trying to make off with it.

The Indians, at that point in time, were not vicious and mean as they were later, when they became aware that the white man was stealing their land and destroying their freedom. However, they did not understand the difference between mine and thine. Anything not in use they would take.

Francis Ann (Sherwood) Simmons, 1803-1882. Mother of Margaret (Simmons) Patton Mills Welch, 1838-1919.

The dried peas which the settlers received by bartering with Indians was a real blessing and probably saved them from hunger in the winter months. They had used up more of their supplies than they had expected on the trip. The farmers in the Pendelton area still raise these same white peas today. Not as a big cash crop but to maintain the quality of the land. They are very good for eating and the straw is excellent sheep feed.

It took a month to make the trip down through the Gorge to Portland. They were not at all impressed by the muddy messy town that lay at the junction of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. It was called Mudville. They had not traveled all summer to make their home in such a mess, so they continued on, and on October 1893, Margaret’s Dad, Ben Simmons, filed for his homestead in Yamhill County. They had reached the promised land, where there was a good water supply and plenty of grass for the cattle.

On 15 October 1855, at the ripe age of 16, Margaret married John A. Patton. He was seven years her senior and was of the well-to-do Patton family, who had come to Oregon in the 1850s. He had a good farm and owned horses and cattle, so he was considered will-fixed.

The couple had four children: Philena Polly, born 1856 (maternal Grandmother of Myrtle Stark Bighaus); Benjamin Robert, born 1857; John Newton, born 1860; and Emerson Grant, born 1863. Their home was in the Beaverton, Oregon area.

One night in December 1864, Margaret’s husband, John Patton, came home from a trip to the wild and wicked town of Portland. He had been hitting the bars too freely and was not able to get into their bed. The beds in those days were quite high and trundle beds for the children were slid under the bed by day and pulled out at night for the little ones to sleep on. He couldn’t get into his bed so he slept on the floor. In troubled sleep, he rolled into the fireplace and his shoes caught fire. Before Margaret could get his shoes off, his feet were badly burned. Infection set in and he died on 23 December 1864. What a miserable Christmas that must have been for Margaret, and her four young children. Philena was not quite nine years old and Grant, the youngest, was one and a half.

It must have been a very hard life for a young widow with four children and a farm to take care of. Less than a year later she married D. E. Mills, a teacher, an educated man. To this marriage one child, John Henry Mills, was born. Henry always had such funny stories and kept us in a fit of laughter whenever he came to our house. However, the Patton family, who considered itself to be the aristocrats of the Northwest, couldn’t understand how a woman who carried the great name of Patton could forsake that noble name and marry a commoner; although he probably had more “book Learning” in his head than all the Pattons put together. They began to harass Daniel Mills; and he, being an intelligent, sensitive man, couldn’t handle it. He disappeared in the great unpopulated area and Margaret never knew what happened to him. In time she secured a divorce on grounds of desertion.

According to the Simmons family history book, written by Helen Maxwell Graham, it seems that Mr. Mills joined Custer as a Chaplin and is believed to have died with Custer in the Battle of the Big Horn.

[Comment about the death of Mr. Mills, by his great-grandson: The Simmons family history makes the claim that Daniel Mills then went on to be a chaplain in the US Army and died with Custer at the Little Big Horn. This is clearly a romantic myth that Margaret fabricated to explain Daniel’s absence to her many curious children. My father, John Mills, said his father, John Henry Mills, said that Margaret repeatedly relayed this story to her children to the point that it was regarded as absolute gospel within the Mills Family.

Joel Mills, descendant of Daniel Mills, states that “After leaving Margaret, he settled in Southern Wisconsin where he was a respected school teacher and lived to the age of 84”.]

Again she was a widow with a farm and now five children. She obtained as a hired man, Rostin C. Welch, a young soldier who had just recently been mustered out of the Union Army. He was a hard working young man and got along with her and her children, so on 21 February 1872, they were wed. Their children were: Edwin, born 1872; Fredrich, born 1874; Daisy Dee, born 1877; and Rosie, born 1881.

Her marriage to my Grandfather Welch started off well but his skills seemed to be more in the line of carpentry than in farming; so they rented the farm and he hired out as a builder. There was plenty of work available.

Early in December 1872, the family moved into the old grist mill at Cornelius, Oregon. The old mill had been abandoned and remodeled into a dwelling. It was the biggest building in the settlement.

Shortly before Christmas one of the settlers approached Ross Welch and asked if it would be alright if they held the community Christmas party in their home. It seemed it was a custom to have the Yuletide festivities there. Ross hesitated, saying, “I’ll have to ask my wife.” Margaret had just freshly repapered the walls of her bedroom, with newspapers, so it was all bright and clean. When Ross asked her about the party she said, “Sure, tell them to come. I wouldn’t stand in the way of a Christmas party.”

The neighbor women came and helped put up the Christmas tree. They decorated it with pretty paper chains made from colorful drugstore paper, strung popcorn and they had a lovely Christmas Eve Party.

Two days later, on 27 December 1782, the first Welch child, Fredrich R. was born. Many years later when Ed left a door open and someonewould shout “Were you born in a barn?!” He would chuckle and say, “No, in a grist mill .” By this time the oldest daughter Philena was a young lady of 21 years and a great help to her mother. However, Margaret was soon to lose her good helper as Philena attracted the eye of one big Swede, named Ole Oleson. They were married 22 October 1878.

[Editor’s note: Ole Oleson is the namesake of SW Oleson Rd.]

The Patton family had started to harass the Welch family. Young Ross Welch, although he could neither read nor write, had experience as a soldier for the Union Army, patrolling the north bank of the Columbia River from Fort Vancouver to Fort Walla Walla. He was better able to cope with the situation than was Mr. Mills for his education.

In November 1894, Ross wrapped up the family affairs in the Beaverton area and took his wife, his three children and one stepson, Henry Mills, loaded them into a wagon and took off for Palouse, Washington, where good land was available by the Homestead Act. The family, wagon containing all the necessities for establishing a home in the new area, their horses, and a few cattle were loaded on a barge and they headed up river.

On their first day on the river there was another family aboard. They had a child about the same age as little Fredrich. The two little boys played together and had great fun. The second day the other child was not feeling well and did not come out to play. He did not show again for the rest of the trip so Fredrich had to play with his big brother Edward. They traveled up river on the barge for about a week and then took another week traveling with the horses and wagon to their new location where they filed on their claim in the area of Sprague. By the time they got to Sprague and before they could get a shelter built, little Fredrich was a very sick boy. He died there of diphtheria and was buried in the newly established cemetery at Sprague. Shortly after Fredrich’s death, Edward and Daisy both came down with the dread disease but they survived. Fredrich died on 6 December 1879, just nine days short of his fifth birthday.

This was a very rough start to their life in the Palouse area. However, they proved up on their claim, built a house and barn, dug a well, built corrals for their cattle to hold them at night. In the spring they planted a garden and built a picket fence around it to keep the chickens and livestock out.

The chickens were a very important part of the settler’s livelihood. They not only provided eggs but were always there to serve up as a quick meal in case of unexpected company. One early morning Margaret heard a great commotion in the chicken house. She started for the chicken house and on the way picked up a piece of lead pipe which was lying conveniently nearby. A good thing she had it, as she met a badger coming out of the chicken house with one of her laying hens in his mouth. She was furious and laid it on him with all her strength. Badgers are notorious for being tough but he was no match for Margaret and her lead pipe. She skinned him out, tanned his hide and made it into a carriage robe for one of her daughter Philena’s babies. That is the way to meet the wolf at the door, only this time it was a badger.

They lived well on their homestead until a crooked lawyer “flim-flamed” Ross out of it. The lawyer got him to sign his “X: on some papers which he couldn’t read. They left the homestead and moved to a place which they rented. Ross went to work as a driver on a freighter. His older brother, Ed, owned and operated a freight line from Spokane Falls to Coeur D’Alene, Idaho.

Ross was quite depressed over losing his homestead and found comfort in whiskey. He was a very friendly man and had lots of buddies. When he came home from a freight run he would very often bring along one of his friends. When that happened he would remember to bring home some supplies. If he didn’t bring a friend he would quite often forget the supplies.

One year they had no snow in the winter, no moisture to produce a garden or a crop of hay.

In 1889 they had a very bad year and Ross forgot to bring home supplies too many times. They had no garden and were on the verge of starvation. Margaret loaded up her family, wagon, and belongings and they returned to Oregon, to her farm in Patton Valley.

Here they lived until the house burned in early 1890. They then moved into a house with Margaret’s second son, Newton Patton. Newton was a fireman with the Portland fire department. One morning after a fire in downtown Portland, Margaret called her son Newton to breakfast. No answer and after the second call she went to check. Newton was dead; it was 25 September 1891. He had left his property to two children of his brother Ben with Ben’s wife as administrator. She gave them notice to move.

In the late 1890’s Margaret’s three sons, Grant Patton, Henry Mills and Ed Welch came to fish in the East Fork Lewis River. They stopped at the Haggard place. Haggards were former neighbors from Clark County. He gave such a glowing account of all the wonders of Clark County that Ed was sold on this area.

In 1900 Margaret and her son Ed moved to Clark County to what was called the North Whipple Creek area. Later it was known as the Pioneer area. At first they lived in the Shonassey House and built a barn, then a milk house which they called the dairy, and a chicken house. Ed had his sleeping quarters in the dairy and Margaret had her tier bed and belongings in the chicken house.

Ed milked a few cows. The milk set in grey granite milk pans to let the cream rise. Margaret skimmed the cream off the pans of milk and churned butter in a rocking barrel churn. She worked it out carefully to get all excess water out and salted it well. Once a week, Ed drove to Vancouver to trade the butter for supplies. Ed had a little green chest which they packed the packages of butter in to take to town. Everything that came in contact with the milk, cream or butter was carefully washed and scalded with hot water from the black cast iron tea kettle.

It was said by some neighbors that Ed Welch had the fastest and fanciest team in Clark County. He drove a pair of Morgan-Hameltonian mares, full sisters. Once he is said to have driven from his farm in the Pioneer area to Vancouver in 45 minutes, which was a speed unheard of at that time.

Margaret had a little side line which earned her pin money. Ed trapped moles around the farm. Margaret skinned the moles and tacked the hides on shingles to dry. After they were dried well she would pack them in a large shoe box and mail them to a fur company back east. When her check came she would have the check converted to hard money and kept it in a flour sack in her dresser drawer. She did not trust checks or paper money. Money had to be solid and ring when you hit it with a spoon or fork.

Her greatest expense was thread, sewing thread and candlewicking thread. She pieced many quilts and also made bedspreads from flour sacks, embroidering many fancy designs with candlewicking. Margaret has been gone since 1919 but some of her quilts and bedspreads live on.

Grandma Margaret was a woman hard of muscle and soft of voice. I remember her holding me in her arms, rocking me to sleep while Mama held Raymond, my brother, who was 13 months younger than me. Her arms were solid, firm, and very secure.

Grandma read to me from the children’s page in the Youth’s Companion, a weekly magazine that came in the mail every Thursday. It was worth walking to the mailbox, three-fourths mile away, to get it. We had to go to Haggard’s Corners to our mailbox. The mailman did not go past our place even though we were on the main drag, the Pacific Highway, until I was a senior in high school in 1929.

Grandma worked in the garden in the spring, summer and fall and in the winter she knitted or worked on her candlewick bedspreads or pieced quilts. Planting the garden was a family project. We all worked at it. I dropped seeds in the hills – 3 or 4 beans or kernels of corn. It was fun. After the garden was planted Grandma took over. She did the hoeing, weeding and harvesting. Grandma picked, pulled or dug the vegetables. The root vegetables were always taken to the well and washed before bringing them in the house.

Grandma cooked all the vegetables and the meats. She usually cooked corned beef or salt pork and sometimes smoked pork. Mama made the bread, biscuits, cakes, pies and cookies. Grandma had three big black iron pots in which she cooked all the vegetables and meats.

Nothing ever tasted quite so good as the first mess of sweet corn. She always brought in and cooked more than we would eat, as soon as the corn was to the firm plump kernel state; and what was not eaten, she dried. The ears were held in her left hand and with her very sharp paring knife she split each row of kernels, she then made a second cut, then with the back of the knife she scraped the cob. This was spread on the old ironstone plates and platters and dried on the open oven door, on the racks in the oven, on the warming oven and on the back of the old wood stove. You might say that the old wood stove was decorated with plates of drying corn. It was watched constantly and stirred often to hasten the drying process. Grandma had her plates of corn which she had cut. Mama had her plates and I had mine. Mama was worried about me using a sharp knife when I was only about five years old but Grandma said, “She has to learn sometime.” After the corn had reached the hard rattle stage, it was put into cloth bags, flour sacks, and hung behind the kitchen stove for about a week. Then the cloth bags were put upstairs.

We had a different method for green beans. When there were fairly large white beans in the pods and the pods had taken on a purple color at the ends, the beans were strung and snapped. They had very firm strings. The broken beans were spread on papers on the floor up in the attic where there was a good circulation of air but out of the sunlight. Two or three times a day we went up to the attic and stirred the beans, rolled them over with our hands so they would dry faster. When they were dry, hard and rattled, they were ready to store in clean, white flour sacks and hung on the wall in the long room.

Pumpkins were dried, also. Papa would bring up several big pumpkins and cut them open on the back porch and scrape out the seeds. Grandma would take the pumpkin halves and with her sharp knife cut them into big orange spirals. The skin was peeled from the spirals and the big orange springs were hung on broomsticks which were suspended from the ceiling by baling wire, behind the heater stove in the dining room. The spirals were turned on the broomsticks everyday so they would dry evenly and in about a week they were dry.

Pumpkin spirals, when dry, were broken up into pieces about an inch long and then also went into flour sacks and hung on the wall. It was no fun to eat, cooked and seasoned with salt and butter, it was yuck! I hated it, but it did make good pumpkin pie and pumpkin bread.

Apples and prunes were dried on racks made of lath with braced corners and flour sacks stretched over the bottoms of the racks. These racks rested on the roof of the bay windows and were reached from the upstairs windows. They were turned daily, too. The clean apple peelings were cooked and strained and made into apple jelly.

Squash were brought into the basement and stored. They never froze and we ate squash all winter. If the squash had to be cut up with a hatchet, they were good. If the squash had to be cut up with a knife I wouldn’t even taste them for I knew they tasted like pumpkin.

Potatoes, too, were stored in the basement. They were the mainstay of our diet. We had potatoes three times a day – boiled for dinner at noon and for supper and breakfast warmed in a frying pan with a little “drippings.” We always had “mush” for breakfast and sometimes pancakes, but always potatoes.

In the summer blackberries were our big fruit crop; the little wild blackberries, of course, not the Himalayas or Evergreens. We made almost daily trips into the woods; Grandma and Mama with their ten pound lard buckets and I with my little three pound lard bucket. Once when Grandma and I went out into the swale along the south side of Papa’s place, we took along a sandwich for our lunch. We sat down on the ground with our backs to a big tree to eat and rest. When we went to get up Grandma couldn’t get up. I took her hand and pulled to try to help her, but no good. I was scared. She told me to go back to the barn and get Papa. I was afraid I would never find my way back to the barn or, if I did I would never find my way back to her. I wouldn’t leave her. I pulled and she struggled and finally she got up. We finished filling our buckets with berries and we went home. I was one frightened little girl.

We always expected to get about 100 quarts of blackberries canned. The orchard behind the house was quite young then and we did not have too many apples but we made good use of what we had. First the Yellow Transparent followed by Gravenstines, Dutchess and Astrachans. Then came the winter apples. The summer apples we ate all we could and then dried what we couldn’t eat, none were wasted. The winter apples Papa picked and stored in the basement.

On winter afternoons before the darkness settled down, Mama and I made a trip to the basement and brought up a grey granite milk pan full of apples. In the evening, either Grandma or Mama would read aloud to the family and the others would peel apples and pass the juicy, shiny apple quarters around. Oh boy, was that fun! That was our evening entertainment before radio and TV. Most of the time, Grandma read. I liked Grandma’s reading better than Mom’s because she read slower and I could understand it better.

While the war was on Grandma sat and knitted socks for the soldiers in France. She made a few sweaters but mostly she knitted socks of ugly brown. They called it khaki yarn. But whenever I took one of my little story books or the Youth’s Companion to her and said, “Grandma read to me,” she laid aside her knitting and would read me a story.

One day she got a pair of No. 6, yellow celluloid needles and gave them to me and said, “It’s time for you to learn to knit.” She held my hands and showed how to cast the yarn and take the stitches off the needle and so she started my knitting career; I still have the needles.

Papa sold the timber off his land to the Toby brothers about 1916. They built a sawmill on the north side of the place complete with cook house, where Walter Toby’s family lived, a bunk house for the men who worked there, a barn for the horses which pulled the logs over the skid roads to the mill pond. There was a good, strong, year-round creek that ran across the north side of the place. Grandma warned us that when the timber was gone the creek would go dry and it surely did. How did she know?

The mill was doing quite well until America got involved in World War I and labor costs went sky high. The Toby’s had their lumber and railroad ties contracted at a set price and when the labor went up they couldn’t make it so they sold out to Walter Crabb and William Zimmerly. Crabb operated the mill and Zimmerly was in charge of the logging.

On one dark, foggy day in November 1918 the news came over the phone, as all the news did in those days, that the war was over. Grandma answered the phone and I will never forget her rushing out to the back porch and shouting “Hooray, hooray, the war is over!”

The pressure was off and she did not need to sit constantly knitting socks for the boys in France but the damage was done. Arthritis had overtaken her. They called it “rumatiz” but it was really arthritis, and she would never again tend her garden. As the winter progressed her condition worsened.

Once they called the doctor in Ridgefield, Washington. Dr. Stryher was gone to the war to take care of our soldiers. A kooky substitute doctor was in town at that time. He came out once, but the second time he was called he never came. He was a poor excuse for a doctor anyway. People said he was on dope.

Neighbors came to “sit with her.” Aunt Rosa and Aunt Daily came, Uncle Henry came. Mrs. John Johnson walked through the woods carrying her lantern to sit with Grandma. It was at least two miles through the woods full of coyotes and all kinds of scary creatures. The word neighbor was very meaningful back then. Oh yes, Uncle Ben was there, too. He came from over in Raleigh Hills, area (Portland). He was a wonderful uncle. He wore a long tan duster coat with big pickets and always brought candy in those pockets.

On 13 February 1919, Grandma, Margaret (Simmons) Patton Mills Welch, passed away. The Ridgefield undertaker came and took her away. He brought her back in a big grey box. They put the box on the front porch. A tall man in a long black coat stood on the porch and talked to all the people who gathered in the front yard.

Uncle Ben made a trip to Portland on the stage and brought back a floral piece made of white lillies and some green stuff. I picked all the purple violets that grew on the north side of the front steps. Mama took the lid to the big shoe box and filled it with moss from the woods, then she stuck all the violets in the wet moss. That was all the flowers.

After the man in the black coat got done talking they loaded the big box into a fancy wagon, the hearse, and put the flowers in too. A pair of black horses pulled the hearse. The family followed in Uncle Fred’s Studebaker car and the other people followed in other cars as we drove slowly down to the old Pioneer Cemetery in Ridgefield, Clark County, Washington.

They put the box down in a big hole in the ground and covered it with fresh dirt and piled the dirt up in a neat mound. Then they put the lillies which Uncle Ben had brought and the pillow of violets on top of the mound. Then a very pretty lady in a dark blue suit stepped up and laid some big, long sword ferns, from the woods, all over the fresh mound of dirt. It was covered with the pretty green ferns. I didn’t understand but I felt so much better. Later I learned that the pretty lady was Emeline (Brothers) McKee, wife of Nels. She was a one-woman Red Cross Chapter. She was always there, come fire or flood, sickness or death. She always found a way to bring help and comfort when there was a need. There was so much I didn’t understand. Everybody was crying but I didn’t cry. Not until after a while when Mama read to me, then I cried because I wanted Grandma. Then I really understood that Grandma was gone.

[These stories were written by Reta E. Welch, in 1986, for the heritage of the family, to remember how life was several generations ago. It took Reta four months to finish. The article was distributed to family via Lela Annette Sederburg-Miller, a granddaughter of Reta.]

A Long Hard Trip

[Written in 1986 by Reta Welch, granddaughter of Margaret Simmons.]

It was a long, hard trip across the plains in the summer of 1853. The cows and young stock had a chance to nibble a little grass as they traveled, but the pair oxen only had a chance to eat when they stopped for the night or occasionally after a very hard stretch of road when they were unhitch and let to rest.

So by the time they got to the Rocky Mountains, the oxen were in really bad shape. One by one the oxen died as their poor feet, cut by the sharp shale rocks, got infected. The settlers skinned the fallen oxen, partially dried the skins over the back of the wagons, wrapped these half dried skins around the feet of the cows to make emergency boots, and the cows brought the wagons through the last of the journey.

Great Respect for Newsprint

[Written in 1986 by Reta Welch, granddaughter of Margaret Simmons.]

With the pioneers having great respect for newspapers it is easy to see why the printing press of early times seemed to rule the country. Everything that appeared in print was taken for gospel truth.

No newspaper was ever burned as long as Grandma Margaret lived. The weekly Columbians were piled up, back under the roof upstairs.

Newspapers were used in several thicknesses to paper the inside of houses. This gave quite good insulation and gave the rooms a clean fresh look. As the papers got yellow with time, a new layer could be tacked over it.

Newspapers cut in scallops and scrolls were used to decorate shelves. Also, newspapers were sometimes cut for placemats at the children’s dinner places to save the tablecloth. Nothing was wasted.

Where did all these dates come from?

[Written by Reta Welch in 1986 (granddaughter of Margaret Simmons).]

If you are wondering where all the dates of births, deaths and marriages came from, about the Margaret (Simmons) Patton Mills Welch family, I will tell you.

They came from the pages of the Family Records – marriages, births, and deaths in the family Bible. The Bible was a wedding gift to Margaret from her parents when she married John Patton (Great-grandparents of Myrtle Stark Bighaus) on 18 January 1855.

The Bible and a few other precious belongings were saved from the 1890 fire that destroyed their home.

The Bible is faded and worn, and the lower front corner is burned off for about an inch. How lucky are we to have it!

Patton Valley, Oregon

Patton Valley is located in Washington County near Carlton, Gaston & Yamhill.

Patton Valley was named for William and Mary Patton who relocated there from Missouri. In 1850 the Patton wagon train came to Oregon. They all settled near Carlton where they took up their land claims. They lived in a community they called “Puckerville” because they were all puckered up so closely together.

William Patton was a cabinet maker. In 1859 he moved his family to a valley west of Gaston which was to be named for them and purchased 600 acres. The first house on the William Patton farm was a log cabin. It was “forted,” having holes at the corners for guns, in case of an Indian uprising. None ever came, but the neighbors were warned to come there for protection if needed.

William Patton was born in Brown County, Ohio, 4 Oct.1807, and died 24 Aug.1888 in Forest Grove, Oregon. His wife, Mary Sherwood, was born in Indiana in 1814 and died in 1906. They were married in Montgomery County, Indiana, on 11 June 1833. They had five children: Frances, Robert, Matthew, Sarah and Jane. Their son, Robert Patton, continued to live in the area for many years.

It is interesting to note how much earlier that area was populated compared to the northern regions of the West Oregon Service territory.

[By: Tracy Kuloneli-Hanchett

Record added: Jan 05, 2008

Find A Grave Memorial# 23755928

Debbie Bighaus-West: I read that the house still exists and that it survived a car crash!]

Pingback: April 2016 News | Garden Home History Project

My mother Olive Wolf (Gertsch) used to stay with Polly Oleson in Seaside by way of the train for the summer and help around her house there in the city. Then the next year Olive’s sister would stay at her Grandmother’s place also by way of a train. Her name was Carline Wolf (Janzan). She was born in 1917 and my mom was born in 1914. Also had a brother named Sig born in 1915.

All have since passed away.

Pingback: January 8, 2019 – Historical Reenactment | Garden Home History Project

Matthew Patton (1805-1892) was the son of Robert Jesse Patton and Eleanor Evans. William and Mary Patton who emigrated in 1850 were not his parents as stated in this article.

Thank you Stephenie! We’ve made the correction.